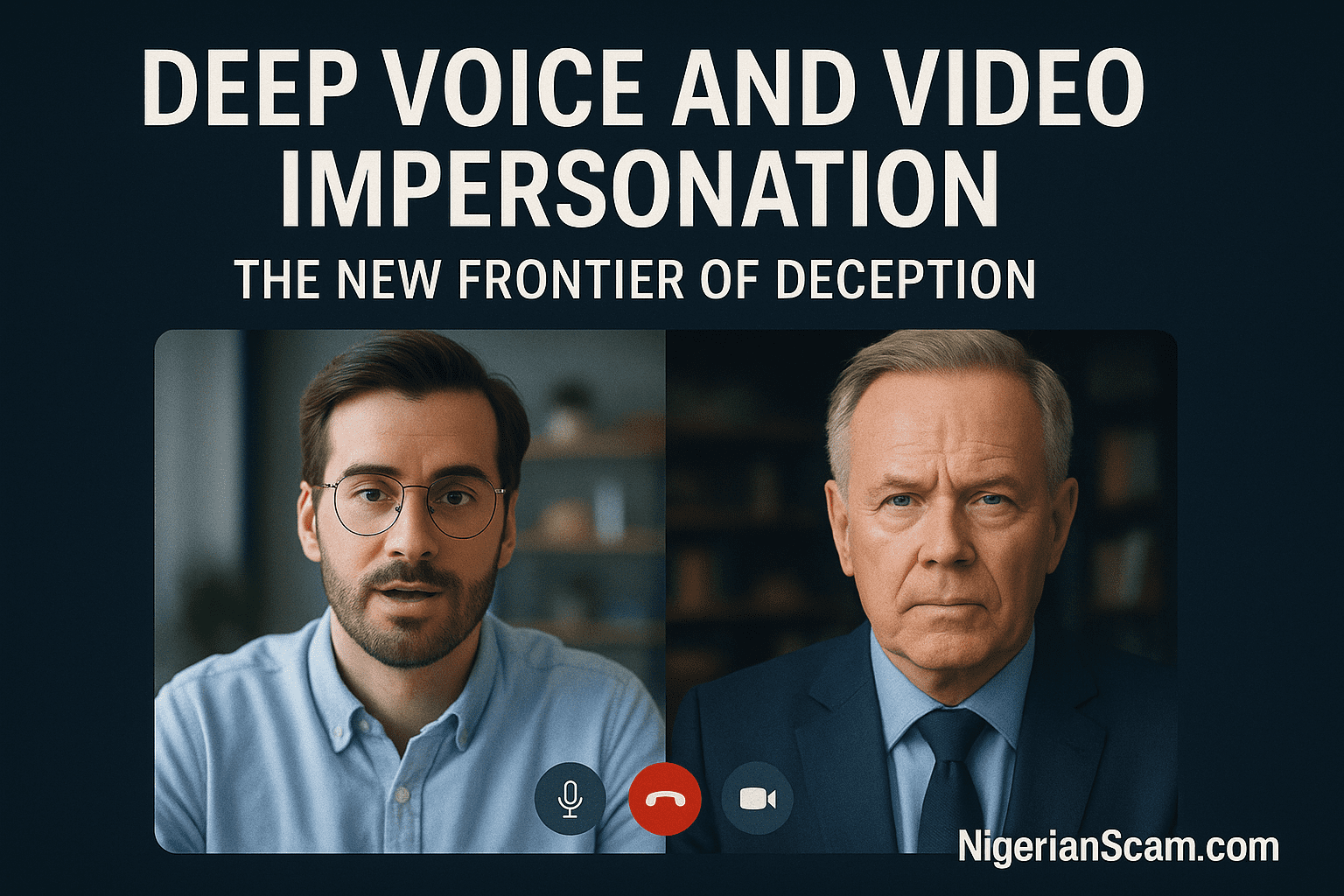

The line between reality and fabrication has grown dangerously thin. What began as a novelty—AI-generated voices and realistic digital avatars — has become a potent tool for modern scammers. Deep voice and video impersonation scams use artificial intelligence to clone a person’s speech, tone, and even appearance, creating audio and video messages that look and sound authentic.

Victims often believe they are hearing or seeing a trusted individual — a colleague, family member, or company executive — when in fact they are interacting with an AI-generated imitation.

How Deepfake Technology Works

Deepfake technology relies on machine learning models trained on vast amounts of audio or visual data. When enough samples of a person’s speech or face are collected — through social media posts, YouTube videos, or even brief phone calls — AI tools can reconstruct a digital version of that individual. This “clone” can then be made to say or do anything, complete with matching facial movements and realistic background noise.

While such technology has legitimate uses in film dubbing or accessibility tools, its misuse for fraud has expanded rapidly since 2022. Scammers now deploy voice clones to bypass identity verification systems, persuade employees to make urgent transfers, or trick family members into sending money.

Common Scenarios and Real-World Examples

- Corporate Fraud: Employees receive a call or video message from what appears to be their CEO requesting an urgent payment. The voice matches perfectly, the tone is familiar, and the background even resembles the executive’s office. Several high-profile companies have lost hundreds of thousands of dollars this way.

- Family Emergency Scams: A parent or grandparent gets a desperate voice message from a loved one claiming to be in trouble — arrested, hospitalized, or stranded abroad. The voice sounds authentic, and the caller ID might even match, thanks to spoofing tools.

- Celebrity and Influencer Imitations: Deepfake videos featuring well-known personalities promote fraudulent investment platforms or crypto schemes. Many victims have trusted these ads because of the apparent endorsement by a public figure.

These impersonations are nearly indistinguishable from real communications, making them among the most psychologically manipulative scams of the digital age.

Why Victims Fall for It

Human trust is built on recognition — of faces, voices, and emotional cues. Deepfake scams exploit this instinct. When a familiar voice pleads for help or a known supervisor gives instructions, the brain’s critical filters momentarily drop. Combined with social engineering tactics — urgency, authority, and emotion — AI impersonation becomes extraordinarily convincing.

How to Protect Yourself

- Verify Before You Trust: If you receive an urgent or emotional message, confirm it through another channel. Call the person back using a verified number or contact them in person.

- Use Secret Phrases: Families and businesses can agree on a code word or question that must be answered before acting on requests involving money or sensitive data.

- Educate Employees: Corporate awareness training is crucial. Staff should learn to question unusual requests, even if they seem to come from leadership.

- Secure Your Digital Footprint: Limit how much personal audio or video content you share online. The less material available, the harder it is for AI to create a convincing clone.

- Adopt Detection Tools: New software can analyze recordings for signs of manipulation, such as unnatural blinking patterns, audio artifacts, or mismatched lip movements.

The Ongoing Challenge

Deep voice and video impersonation represent one of the most complex threats in modern cybercrime. As AI improves, detection becomes more difficult. Regulators and tech companies are racing to create watermarking standards and authentication systems that can flag synthetic media before it spreads. Yet personal vigilance remains the best defense.

This emerging form of fraud underscores a simple truth: in a world where seeing and hearing are no longer believing, skepticism is not paranoia — it is protection.